Among the features of a global agenda centred on a finance-philanthropy-development nexus is a collaborative approach to advancing digital financial inclusion. The digital form of financial inclusion builds on earlier development interventions centred on microcredit and its more expansive version: microfinance. While these earlier interventions came across as grassroots initiatives to counter the exclusionary nature of national financial systems, they quickly became mainstream.

This process of mainstreaming is reflected in the Sustainable Development Goals for 2030 — in which financial access is repeatedly mentioned — and has largely been pushed by the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor or CGAP. This institution has operated out of the World Bank headquarters in Washington D.C since the 1990s and describes itself as a partnership of more than 30 leading development organizations, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Credit Suisse, KfW, and the United Nations Capital Development Fund. Through extensive commentaries on financial inclusion strategies including data analysis, and by formulating guidance on regulation and standards, the CGAP has been instrumental in making financial access for the poor an integral part of national and global development agendas as well as the global financial architecture. The close connections between microfinance institutions in developing countries, global philanthropic foundations, and the international asset management industry thus reflect and arrangement in which philanthrocapitalists have taken on the responsibility of funding the borrowing needs of the poor.

The success of the CGAP offers a template for other organizations based on global partnerships to target developmental goals. The provision of legal identity for all, including birth registration is one such target, articulated in Goal 16.9 of the SDGs 2030. For this, the World Bank has led another project; the ID4D initiative, that frames digital identification technologies as having transformative potential for poor countries. The objective of this initiative is to utilise private-partnerships to establish digital identification systems for the delivery of basic services to the poor. At the core of this strategy is the ID4D Multi-Donor Trust Fund. Established in 2016, it is supported by several organisations including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Omidyar Network and the Australian Government.

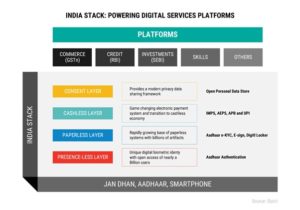

Critical scholars are apprehensive about various aspects of the wider digital identity project; primarily about the right to privacy, but also on inequalities driven by race, ethnicity, and gender. These echo earlier concerns associated with financial inclusion strategies, particularly because indebted poor people regularly become income streams for large financial institutions. As such, financial inclusion strategies are often a form of financialisation; and like other forms of financialisation they replicate inequalities. Because the relationship between financial access and digital identity has tightened, it has become easier for large financial institutions and technology companies — or fintechs — to monetise digital footprints of those who use digital technology for financial transactions and also to access welfare and other government services. This relies on what fintechs call a ‘Stack model’ and advances what has been described as digital financialisation.

My argument is that security, and not just financialisation, is the appropriate lens to examine technologies for financial access. Whilst endorsed by the nexus of finance, development, and philanthropy — ostensibly to facilitate welfare policies — such technologies are also part of a global security imperative. This is perhaps best reflected in the objectives of the Financial Action Task Force or FATF, which is a G-7 body that seeks to counter terror finance and money laundering. Examples from India and Pakistan show how such strategies drive collaborations between governments and fintech companies that complicate policy transparency

Figure 1: Digital verification-based Stack model.

Source: https://pn.ispirt.in/the-best-way-forward-for-privacy-is-to-open-up-user-data/