In December 2023 I travelled to Shetland for two weeks. The aim of my trip was to conduct fieldwork research for a project studying small business lending in remote island communities. During my stay, I interviewed professionals from the private and the public sector, including local banks and business consulting, small business owners, and public officials involved in initiatives to support small businesses.

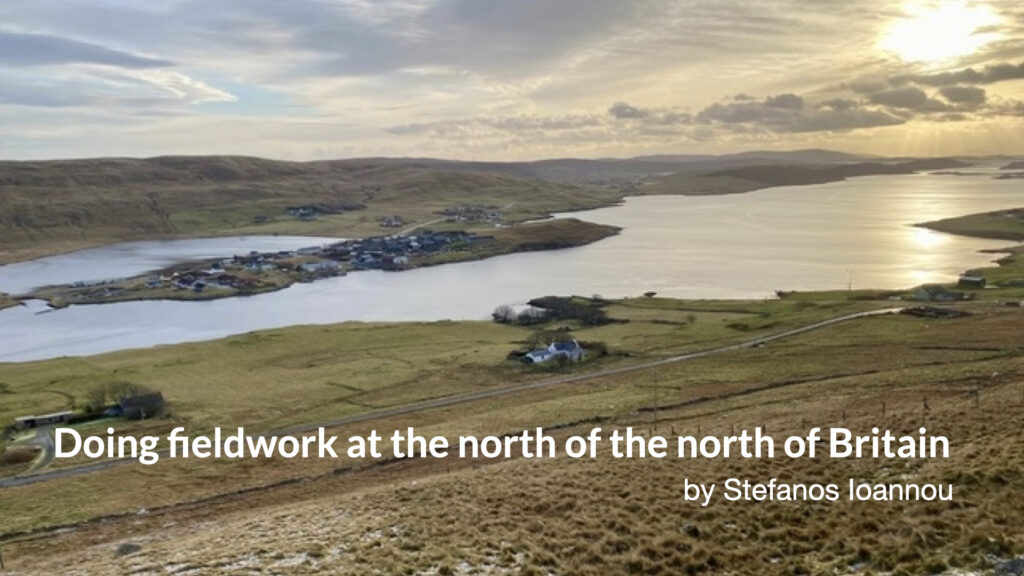

Many people, even from the UK, would struggle to locate Shetland on the map (if you are still wondering, look at the very north of Britain, and then look a bit further north of that). Some might know Shetland from the BBC crime series (in which case, the first part of a stay in Lerwick, the capital of Shetland, is to spot the house of Inspector Perez!). Others might know Shetland for its wool and ponies.

Many people, even from the UK, would struggle to locate Shetland on the map (if you are still wondering, look at the very north of Britain, and then look a bit further north of that). Some might know Shetland from the BBC crime series (in which case, the first part of a stay in Lerwick, the capital of Shetland, is to spot the house of Inspector Perez!). Others might know Shetland for its wool and ponies.

Shetland is not like any other part of Scotland, in that you see little of the dominant Scottish stereotypes, be it haggis, kilts and bagpipes. Partly, that’s explained by Shetland’s historic ties to Scandinavia. Part of Denmark until 1469, Shetland was offered to Scotland, together with Orkney Islands, as the dowry of Princess Margaret of Denmark in her marriage with King James III of Scotland, due to Denmark’s lack of money. Denmark was to unmortgage the islands and take them back once the Danish king, Christian I, found the money to cover his daughter’s dowry. Something of an early form of financialisation. Payment never happened and Shetland turned Scottish.

Today, Shetland faces several challenges different to the rest of Scotland and the UK. Rather than unemployment, which is the lowest in Scotland, their main challenge is a shortage of labour. Shetland also has a major lack of accommodation. As one interview partner put it- perhaps with some element of exaggeration- Shetland doesn’t have houses to host workers and workers to build houses. Meanwhile, the role of the public sector is pivotal. The local council is a major provider of financial support for local businesses, in the form of commercial loans and grants. It is also the sector that has developed the area’s key amenities, such as Lerwick’s cinema and arts centre.

All my interview partners confirmed the importance of physical presence in Shetland for understanding the local socio-economic environment, be it for lending, or for designing economic policy. For lending, interview partners repeatedly highlighted the significance of tacit knowledge. When asked whether they trust the bank they work with, several business owners responded they trust the person they deal with, rather than the bank itself. On economic policy, an interview partner surprised me by claiming that inasmuch as decisions are to be taken outside Shetland, they would much rather be taken in London rather than Edinburgh; the argument being that whereas policy makers in Edinburgh think they know Shetland, the ones in London at least know they do not know much about it.

Shetland is also characterised by a strong sense of community. Scotland’s official Household Survey confirms Shetland’s positioning at the top of Scotland in terms of community belonging, together with Orkney Islands. In my fieldwork, several interviewees used the term ‘community asset’ to describe certain local businesses. In Cullivoe, for example, Shetland’s northernmost town, the local council recently purchased the main store of the area, which was about to shut down. When I asked an interview partner from the council why they decided to buy a private shop, the response was that for them the shop was not just a place to buy stuff. It was also a place for locals to hang out.

Shetland also is home to financial innovation, broadly defined. Several interviewees mentioned the case of a restaurant which raised funds via local crowdfunding, offering to funders a series of meals once open for business. A whiskey distillery recently raised its initial round of funds from local and other investors, offering in exchange barrels of whiskey to be held as financial assets; in other words, to be stored for free at the distillery under the ownership of the investors, while allowing their value to fluctuate according to global whiskey prices and the development of the distillery’s brand (yes, there is a secondary market for whiskey!).

From a practical perspective, doing fieldwork in a remote area like Shetland has several differences compared to fieldwork in urban areas. First, the available pool of professionals to reach out to is much more limited. Secondly, the small size of the population makes it more challenging to find contacts from one’s own network. On the other side, the fact that locals tend to be familiar with each other enables a stronger snowballing effect once an initial set of contacts is established. Fieldwork in such areas also requires flexibility in the interview schedule. For one, Google is not entirely reliable in estimating driving times, e.g. by not accounting for herds of sheep blocking the road as one heads to an interview appointment. Meanwhile, an initial email to rural business owners for arranging interviews can end up with an invitation to the weekly community lunch. Can’t say no to that!